Parenting

Try only speaking to children in the form of questions

- ex. Instead of: "Brush your teeth! Get to bed!", try:

- "What time is it?"

- 9:00

- "And what do we usually do at "9:00?"

- brush our teeth "Well then, are you ready to brush your teeth?"

Remember, when toddlers make you angry, they are not giving you a hard time; they are having a hard time.

Favor growth, effort praise over intelligence praise

- fixed, intelligence praise- “That’s a really great score; you're so smart”

- growth, effort praise - “That’s a really great score; you must have really worked hard.”

"Our kids do not earn an allowance, but instead earn a commission by doing chores and illustrating good behavior. The kids understand that they lose money by contributing to a complaint jar every time they whine about something before trying to solve the problem first."

Ask "What did you fail at this week?"

- This prompts them to think about what they didn't do well this week, and prompts them to seek for learning opportunities in those failures

because firstborn children start life as only children, they initially identify with their parents. When a younger sibling arrives, firstborns risk being “dethroned” and often respond by emulating their parents: they enforce rules and assert their authority over the younger sibling, which sets the stage for the younger child to rebel.

parents of ordinary children had an average of six rules, like specific schedules for homework and bedtime. Parents of highly creative children had an average of less than one rule and tended to “place emphasis on moral values, rather than on specific rules”

When mothers enforce many rules but offer a clear rationale for why they’re important, teenagers are substantially less likely to break them, because they internalize them.

"Please don’t cheat" they changed the appeal to “Please don’t be a cheater.”

it's more effective to ask someone "did you try your hardest?" than to tell them "you didn't try your hardest".

The ability to visualize is one of the most important things you can foster in someone

- it allows things to come alive. If you can visualize well, a little movie can form in your head, which makes things more vibrant and interesting. This fosters more of an interest in how things work, sparking creativity.

Praising the process

Start to marvel at the workings of your child’s mind. Be curious. Wonder about the “how” rather than praising the “what.”

- ex. Ask, "how'd you think to create it like that?"

When someone asks us a question that indicates interest in our process we feel that we have that person’s full attention, that there’s nothing this person wants more in that moment than for us to expand and share more about ourselves.

The parent is in charge of the decision, the child is in charge of his feelings

When parental arguing is witnesses by a child, it’s not the argument that’s scary to them, as much as it is that no one talks to him about the argument he overheard.

- A child cannot feel safe until he understands what’s happening around him. Avoiding talking to a child after an argument means that a child is left to his own devices to understand what happened; this is too much to manage, and a child will resort to self-blame to gain control.

- When we give a child a story to piece things together, a child feels better because he can tell his alert system, “Now that I understand what happened and feel connected to my safe adult, I’m safe.” There are a few key elements to explaining your arguments to your child:

If you want to be an askable parent (ie. a parent who tells their kids "you can talk to me about anything"), you have to first model the behaviour by sharing with them. Tell them stories about your day, tell them stories about your past. Keep it mundane, but develop the habit of sharing personal information about yourself so that your child really feels like their is no barrier to be able to feel understood and unjudged.

Fostering creativity in a child

The goal for parents shouldn’t just be creating spaces for free thinking, but defining those spaces. Give the kids the heavens, but tether them to Earth.

- ex. Say it’s time for an art project and you’ve provided your kids with paints or colored pencils. Give your kids instructions to draw a sun. Then, excitedly say, “Let’s draw a weird-looking sun with clouds that block it!” or whatever you think is fun and creative. After some time has passed, say, “Let’s share our drawings at the same time!” When that happens, emphasize the originality of the child’s vision. Say, “Look at your sun! Your sun has black and green, unlike the sun in the sky, which is orange and yellow. That’s really great that you’re using your imagination!” By encouraging the kid not be literal, you’re giving the kid a space in which to be creative.

Modeling imagination requires that parents encour

- ex. If you’re building something out of a plastic toy set, you might make a building out of it, but you can also ask your child, "what is the strangest building we can possibly make? What would it look like?"

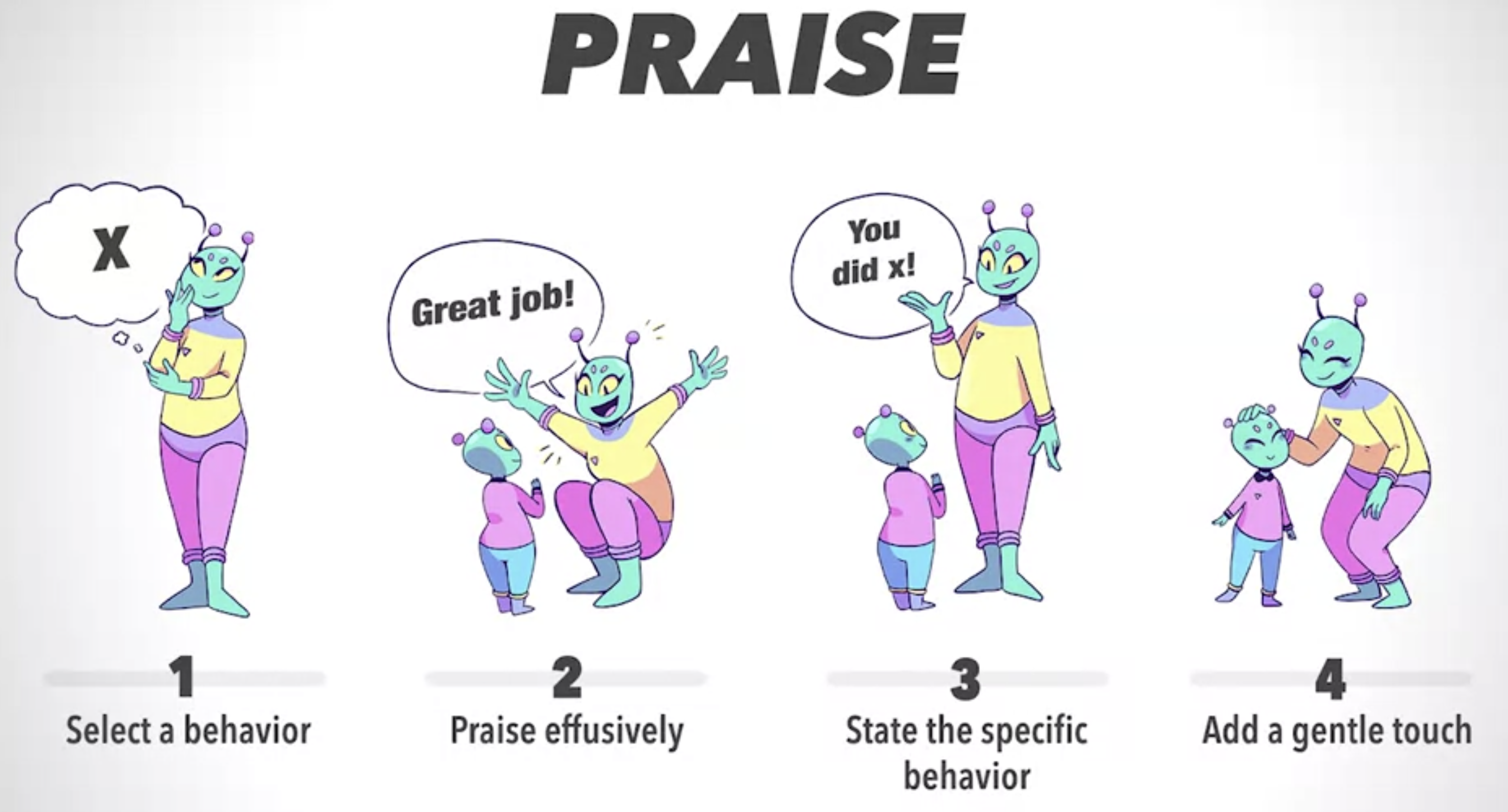

Praise

To praise a child in a way that inspires behaviour change, it should contain all 3 elements:

- it is emphatic. Big smile, use of the hands for emphasis. Loud cheery voice.

- it should make mention of the thing that is being praised

- non-verbal praise component, such as a high-five, a tassle of the hair, a hug etc.

Praising an adolescent (ie. pre-teens and teens) should not be done in an effusive way. Also, the non-verbal praise component should involve no touching (e.g. thumbs up, air high five etc.)

Also, one should determine which action to praise beforehand. Focus efforts on one or two behaviours to change, and praise freely.

- this makes you more likely to notice these behaviours in your child so are less likely to forget.

Praise should be delivered right after the behaviour occurs

Give even higher praise for behaviour that did not have to be preceded by a prompt (e.g. when you didn't have to ask your child to get dressed)

Look for opportunities to mention the good behaviour that had occurred previously

- ex. "Wow! You got dressed right when I asked, just like you did yesterday!"

When using praise to shape behaviour, try to praise as many occurrences of the good behaviour that you can

If a target behaviour doesn't occur often, praise effusively when it does occur. Make a huge deal about it.

- ex. "I cannot believe you did that just like a big boy!". If someone else is around, bring that person in the room tell the person all about the amazingly excellent behavior that you just saw. As the other adult enters the room, you could say, "wait till you hear this! Big boy Caleb did exactly as I asked and right away, can you believe it?"

If the child doesn't co-operate with bigger tasks, get them to do minor things

- ex. ask them to come and give you a hug, then praise "great! you came over when I asked!"

- ex. if your ultimate goal is to get them to put their dishes in the dishwasher, start off by getting them to bring their cup to the sink and build up from there.

Avoiding bad praise

Never connect being a good child with the target behaviour

- ex. "John, you're a good boy because you cleaned your room like I asked"

Never connect your love/happiness for the child with the target behaviour

- ex. "You make mommy and daddy very happy by cleaning your toys"

Never deliver cabooses to praise

- ex. "Thank you so much for cleaning your room. why can't you always just do it when I ask?"

Avoid giving out vacuous and non-specific praise, as it will diminish the value of your good-quality praise. The art of delivering praise is just as much about what praise not to give.

When the child just won't listen

The first step is to try to eliminate the cloud of desperation hovering around the behavior.

tell the child it is OK if she does not do the desired behavior, or, if it’s essential (bathing, for instance), if she does it superficially and minimally.

practice nonchalance in talking about the behavior—a shoulder-shrugging, laissez-faire attitude of staged indifference.

- ex. "Don’t worry about this now; you will be able to do this when you get older," a pressure-reducing antecedent that can actually speed up compliance.

- If this relaxation of the pressure leads the child to do the behavior on his own, the parents should maintain their guise of indifference.

- In most contexts, effusive and enthusiastic praise is best, but this situation is different. Here, effusiveness has become associated with stress and implicit pressure, so instead we need some low-key acknowledgement—a simple "That was good" augmented by a nonverbal adjunct like a pat on the arm or the back of the head, all low-key and in passing.

Offer a choice.

- ex. "can you put on your red coat or blue coat please?"

- ex. "I can help you if you'd like"

Adolescents

With a teenager, any effort to control or even influence facets of the adolescence life could be met with resistance and oppositional behavior

Compromising and Negotating are 2 important tools toward developing your influence over the teenager.

- Compromise refers to the outcome or actual solution that you reach

- negotiation refers to the process of how to get there.

Compromise

Compromising strengthens your rules in areas where you can't be open to compromise.

A good rule of thumb is to err toward compromise on things that could be considered phases. Let your child do things that in a manner of 10 years, they would look back and deny that they ever did those things

- ex. dying hair, dressing goth

Negotation

The opposite of negotiation would be doling out advice and making decisions without any real input from your teenager.

listen to what your adolescent says without jumping in, and withold judgements

Focus on present and not what happened in the past

- even if you are right, being right is jeoporadizing the process of negotiation.

Finally, when it is your turn to talk, provide alternatives and suggestions for how to proceed with the situation.

- Provide a number of options of how to proceed, that might include two or three possible solutions.

- present them in a way that is not authoritative.

- So try not to say anything like, "Here's what you should do" or "this is what needs to happen". Rather, leave with a sentence like, "Here are some alternatives we might talk about" or "have you considered this or that?"

- the adolescent is much more likely to agree to one of your options or generate a compromise based on how you present the possible options and whether choices were involved.

Elements of effective negotation:

- select a time where there is no tension and no decision has to be reached at a particular moment.

- listen without jumping in. Be respectful of the teenager. Focus on the present and completely avoid bringing up what the teenager may have done in the past.

- Stay on topic

- offer possible suggestions when there is a disagreement.

Remember to praise when the child exhibits the good behaviour as a result of the negotiation

Initiating the negotation

Don't be abrupt in bringing up the subject

- ex. "Can we talk about the cell phone problem?"

- bring it up in this way means "I want to talk about something, and this is a problem"

Begin with the mindset, "Here is why I need your help. I would like to reach a solution we can both live with regarding your cell phone use. You have one view, I have another. Let us find something we both might be able to live with and to do together. I know you want to use your cell phone all the time. It is important for me to understand more about this. Tell me how you see this."

- after listening thoughtfully to them, say something like "Here's my view. And let me say this even though you probably know what it is."

- Here to the tone of how and what you say are even more important than the content to keep the negotiation going.

Whatever you decide, this is a trial period, maybe for a week, and then you come together to see how it is going. This gives you and your teen a way out if some part of it is not working, or if there is some tinkering that needs to be done.

Problem-solving

- state the problem

- ex. You might say, "So Jack, is picking on you at recess."

- prompt and encourage the identification of potential strategies or solutions.

- ex. So you say, "What are some of the things you might do to handle that?"

- identify two or three possible ways of handling the situation or general approaches to the problem

- if your adolescent can take the lead on one of these that is better. We want to get them involved in the decision making process. It is imoprtant to not judge their strategy at this time.

- ex. you might say, "Well, one thing we could do would be to talk to the teacher. Is there something else we could do?"

- go through each possible solution one at a time to identify what the consequences would be

- ex. You say, "Okay, one strategy is to go to the teacher. If you went to the teacher what would happen?", and then prompt the same for the next strategy

- choose one of the solutions that is the best of the solutions based on the different consequences.

- ex. You say, "Okay, which seems to be the best solution?"

- simulate

- Try to make this fun and light.

- ex. you and your teen actually role play the best solution. You as a parent play the bully and your child pretends to be himself in the situation and he acts out the best solution. Then you switch roles.

ABCs: Antecedents, Behaviour, Consequences

- source All 3 are critical components to changing behaviour

note: the techniques described are tools that must be used together. One cannot expect results if they are just using one tool in isolation of others.

- also, they must be used consistently. This is precisely why the first element of many of the tools is to "define the behaviour you want to change beforehand".

The tools described showcase examples that are fit for school-age children and younger, but the concepts apply equally well to a person of any age (including adolescents, and even adults). It is how the tools are applied that matters for their effectiveness per age-group

Antecedents

antecedents are various things you can say and do before the behaviour, that increase the likelihood the behavior will occur.

- ex. "If you really loved me you would go to this family event with me."

- A bad antecedent, but an antecedent nonetheless

Antecedents must be combined with consequences in order for them to work, otherwise they won't do much to change a behaviour

Behavior is heavily controlled by antecedents: whatever you do to set the stage for a behavior to prompt it to occur.

There are 3 types of ancetedents:

- Prompts

- Positive Setting Events

- Negative Setting Events

Prompts

Types:

- verbal, like "go brush your teeth"

- physical, such as taking your child by the hand and leading them to the bathroom

- visual, such as brushing your own teeth to show them how

Prompts should be specific

- ex. "pick up all the clothes on the floor and put them in the hamper" instead of "clean your room"

In the learning phase, prompts should ideally happen right before the desired behaviour is to occur

- later on when the behaviour is well developed, you can start asking them to "clean your room when you get home from school"

Prompts should be combined with positive setting events

As a rule of thumb, making the same request twice is fine, but more than that is nagging and should be avoided.

- in this case, instead of nagging, go and help the child out. When you get a little bit of the good behaviour, praise it.

Positive Setting Events

Called "setting events" because they set the stage for the behavior you want.

- We know that the same request may or may not lead to compliance based on how it is delivered.

Examples:

- tone of voice

- formation of sentence

- bending down to their level

- whether or not a choice was presented

- note: offer choices whenever possible

- saying "please"

- offering help to the child to start the behaviour

- playful challenge, along with a mischievous look and pretend doubt

- ex. With a playful smile, "I'll bet you couldn't get your jacket and boots on in under 2 minutes! Only fully grown children can do that! You'd have to be a superhero to be able to do that."

- ex. "now Billy, it is probably too hard to do one more 'calm tantrum', and I'm not sure you're big enough to actually really do that". Following that, "no one on this planet could do it three times in a row, so let's not even try!"

- ex. "Caleb, this might be hard to do. It’s something you will be able to do easily when you’re a bigger boy, but let’s try just for the heck of it."

Negative Setting Events

Negative setting events are indirect antecedents that decrease the likelihood of a behavior, or increase some behavior you really don't want.

- ex. using a harsh tone with your verbal prompt

- ex. limiting your child's choice with certain phrases

- "do it because I said so"

- "I'm the parent and you have to do this"

- ex. showing frustration

Antecedents practice

In front of a mirror, act as if you were giving the prompt to your child, and ask it in 3 different ways:

- as you normally do

- in a way with negative setting events

- in a way with positive setting events

Jumpstarting

Sometimes getting the child to perform the behaviour is difficult because it seems insurmountable in their mind (e.g. starting a school project). We can take advantage of response priming by sitting down with them and starting the project with you and working on it for just one or two minutes.

- After the first step is completed, the child is allowed to stop. That is the critical part.

- You may explicitly offer them the choice to stop the activity, or you may just choose to remain silent and see if they bring it up.

Consequence Sharing

The idea with consequence sharing is that if you have 2 children and want to correct a behaviour in just one of them (ie. the target child), you can offer a positive consequence for good behaviour that applies to both children, but only if the target child performs the good behaviour.

- The reward could be points, or it could be much easier if you use a privilege, such as staying up 15 minutes longer for bed, or hearing a story.

- Pick something that could be used each day.

A benefit of consequence sharing is that siblings end up encouraging the child to do the behaviors often with very specific statements like "do this, and I will help you".

Group Program

A slight alteration on consequence sharing is called a group program, where the difference is that both children must perform the specified positive behaviour.

- this is the preferred way to handle this if both children have the same behavioural issue.

Behaviour

The question of interest is, "how we design the situation to get the exact behaviors we want?"

Shaping, Simulating, and Modeling are 3 different procedures for inspiring the child to partake in the behaviour.

Shaping

Shaping is rewarding small steps that begin to resemble the behaviour you want

- the small step might even be a part of the process, rather than actually doing the behaviour

- ex. if trying to get the child to eat vegetables, just get a small spoon of vegetables and put it to the child's lips.

- ex. If you want child to do homework after school, start with 10 minutes and 4 days/week. Once that is consistent, you can gradually start to increase the amount.

- ex. if you want the child to clear the table, start small. Get them to clear their plate and bring it to the sink. Praise effusively. After a few days of this, get them to start putting it in the dishwasher. Praise more.

- ex. if you want your child to be downstairs ready by 8:00am on school days, break up the larger task of "getting ready" into smaller tasks that are easier to achieve. Consider even moving one component to the night before, such as packing the bag. This gives opportunity to deliver praise and makes for an easier transition the next morning since part of the job is already done, and the grand task doesn't seem so daunting.

If the child does not listen, stay positive with them. Say "here, let me help you. We can do it together!"

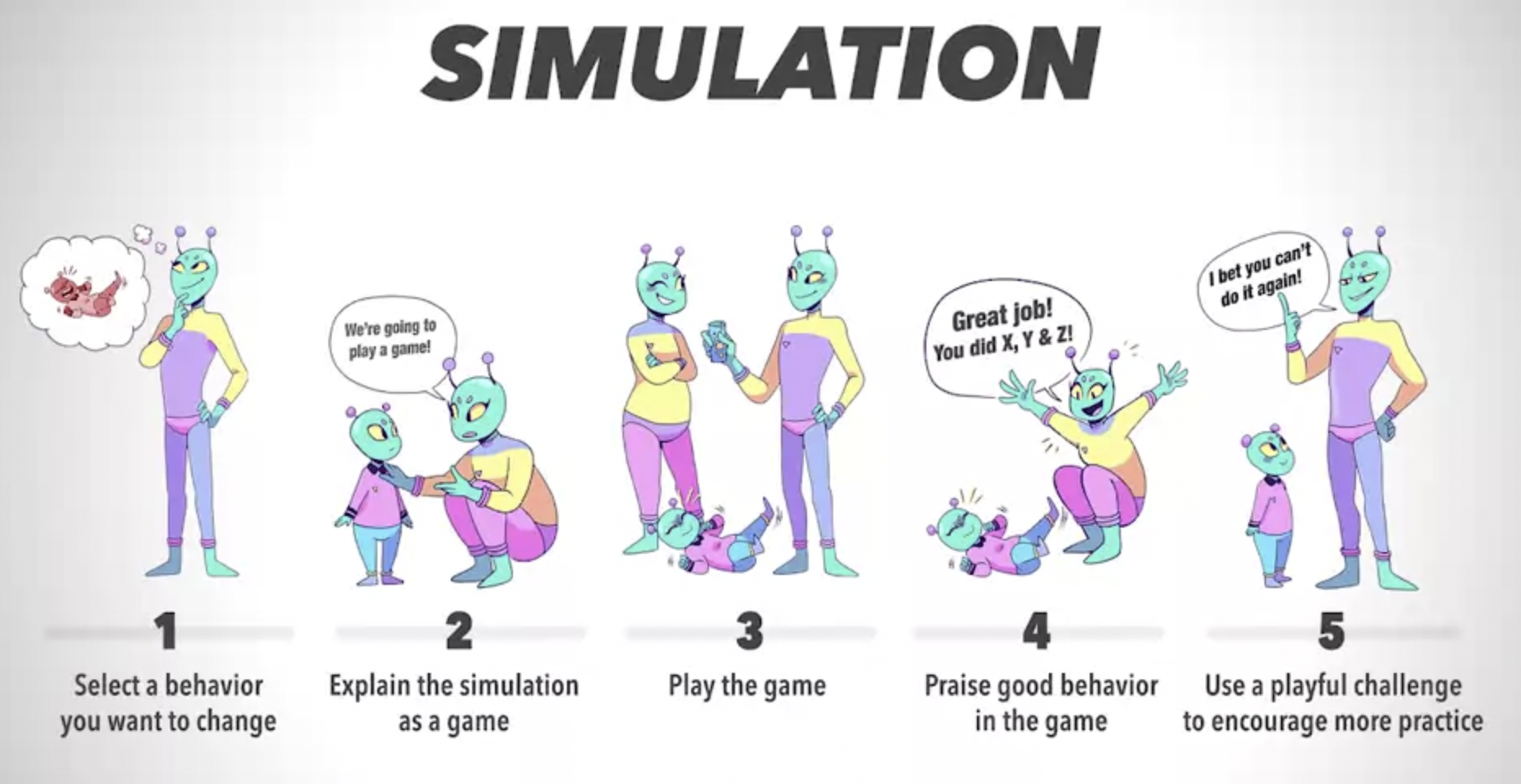

Simulating

Simulation consists of making up practice opportunities to engage in the behavior in game-like, role-play and pretend situations. In other words, doing the behavior under artificial conditions.

- One repeatedly practices the behavior under these artificial or pretend circumstances, the effect is to build a behavior, and the behaviors carry over to real situations, including those you wish to change.

- here, practice refers to the behaviour that you want to occur

Simulating can help both with getting the child to do things you want, as well as not do things you don't want

For simulation to be effective is not only what you do, but how you do it.

you should also make use of antecedents while explaining and doing the simulation.

you can use modeling to show the type of behaviour you'd like them to exhibit.

Play the simulation every day for maybe a week or so.

It's important to do the simulation at a time when there is no anxiety, tension or pressure.

Be sure to praise the good behaviours that occur outside of the simulation

Simulation actually combines a number of tools, including the use of antecedents, praise, point programs, and developing positive opposites.

Examples:

- play the get ready for school game on a Saturday or after dinner.

- play the going to bed game in the morning

Example: Tantrum

"Go to the child and say Billy, I have a game I want to show you, it’s called the tantrum game. It's just pretend and here is how it works, I am going to tell you that you can't do something. I will say you can't watch TV tonight, but this is just pretend, you can really watch TV later, I just want to pretend that you can't do it. Billy, after I see you can't watch TV, it's your turn to have a pretend tantrum. You can say, no, you can get mad, you can fold your arms, but no hitting of mommy, no throwing things, and no shouting. You are just pretending to get mad."

- when the child exhibits the correct behaviour, make sure to praise effusively.

- after the simulation, offer a playful challenge that they can't do it again.

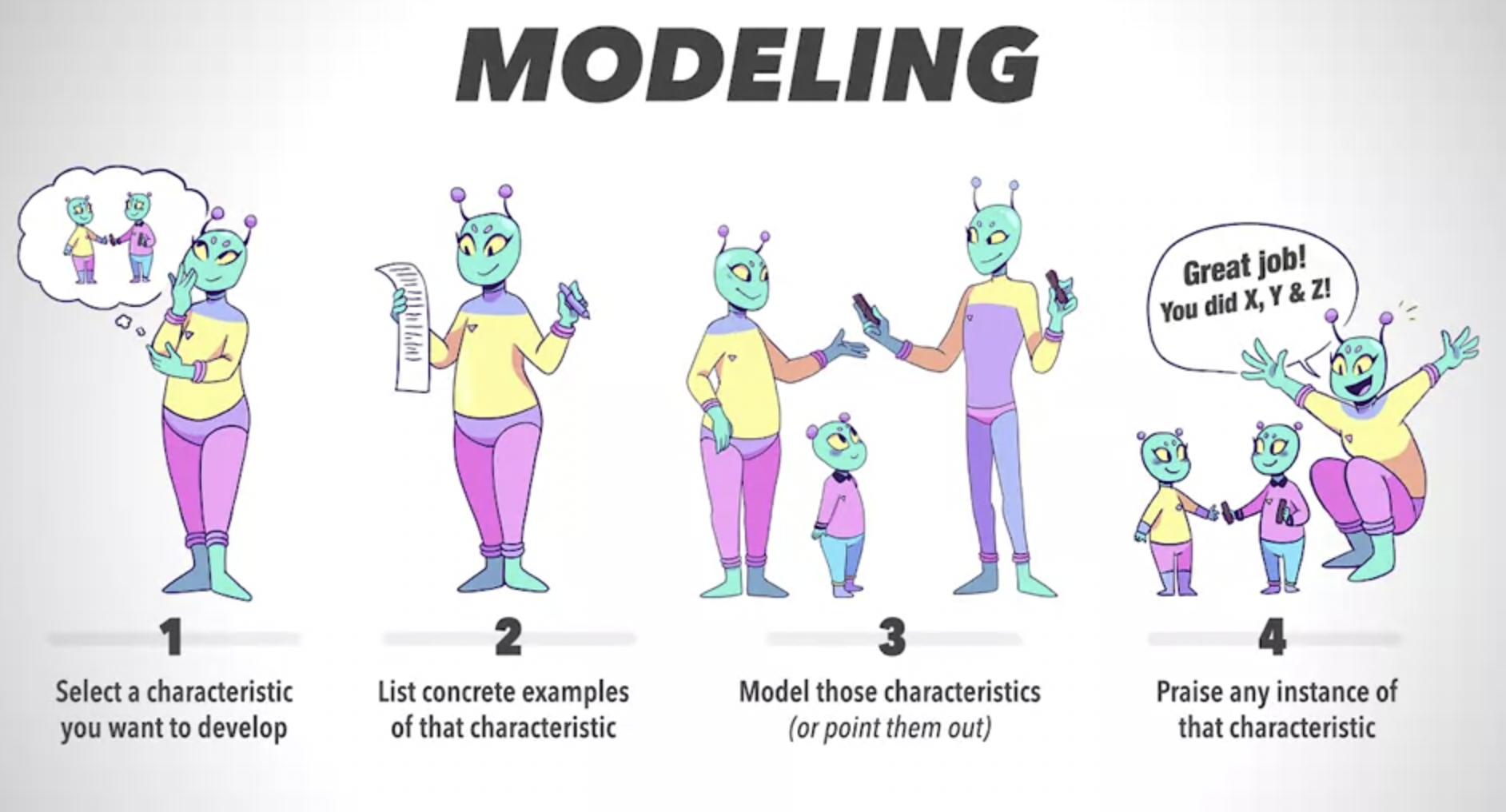

Modeling

Think of modeling as teaching by example.

Modeling can be either accidental or deliberate

- accidental: e.g. using swear words in your speech, reacting angrily at something small

- deliberate: seeking out instances where you can model the behaviour

- Pick a bevahiour to model

- Think of instances that would demonstrate that behaviour

- Model the behaviour in real life

even pointing out 3rd party modeling is beneficial, whether it is in-person or even on tv or a book.

- ex. "It's good that Sam was so loyal to Frodo, don't you think? Frodo knew he could count on Sam, and it turned out to be the sole reason they were able to succeed in the end"

Modelling doesn't have to occur each day, but modelling instances are needed.

Example: Kindness

Say you want to improve kindness in your child. First, you think of instances of that behaviour.

- ex. helping other children, sharing things with other children, comforting someone in distress.

Look for opportunities throughout the day to model behaviour that is indiciative of the change you want to make. Explain the action to your child after you've done it.

- ex. "I just gave this person some money for lunch because they did not have any".

Consequences

Positive Opposites

This is an alternative technique to punishment for correcting bad behaviours.

The idea is to "catch your child being good".

- identify some behavior you want to reduce or eliminate in your child.

- identify what you'd like the child to do instead of that behavior (called the positive opposite, because it's the exact opposite of the behaviour you want to get rid of)

- Sometimes it's the exact opposite and sometimes it's just a more appropriate behavior that you want in his place.

- praising the child when you catch them doing the positive behavior

Developing the positive opposite puts the emphasis on replacing or building the behavior, and now will lead to a decrease in the behavior you want.

Example behaviours and their positive opposites:

- you want to get rid of your children fighting over a TV show.

- opposite: Them sitting and watching TV together nicely

- go to them and say, "You two are playing so nicely. That's wonderful to see you get along so well!"

- you want to get rid of your child throwing his clothes all over the floor in his bedroom

- opposite: Them placing them in his dresser or in the closet where you'd like them.

- you want to get rid of your child getting out of bed again and again.

- opposite: Them going to bed, maybe getting up no more than once and staying in bed.

- "It's so nice the way you went into your room and got ready for bed right away."

- you want to get rid of your child shouting at you whenever you say no to something.

- opposite: Them expressing anger calmly and doing what you asked.

Due to negativity bias, it's difficult to notice your child's positive opposite behaviours. This is something that must be overcome to make effective use of positive opposites.

Avoid focusing on the negative

- ex. endlessly explaining to a child why their behaviour is wrong

Point Programs

Give your child points for good behaviour, and allow them to spend those points on privileges/toys that they desire.

5 ingredients are necessary:

- Specify the exact behaviours that earn points

- ex. completing 15 minutes of homework

- ex. putting your toys back into your room

- ex. getting into bed by 8 p.m

- Choose a medium for disbursing the points

- ex. checkmarks, stickers, tickets

- Devise a way to keep track of points earned and keep it visible for the child

- Specify how many points each behaviour earns

- Develop a reward menu, that specifies what the points can buy and what their costs are

- consider having the child's input on what kind of rewards there can be

it's important to have small rewards that can be bought right away without saving up.

Avoid food rewards

At the end of each day or whenever convenient, choose a time when they can buy something.

Whenever points are earned, make sure to praise so that the child knows exactly what they did to earn the star

If the child does not perform the desired behaviour, don't nag or show you are upset, but calmly state, "You did not get a point today, but maybe you can earn one for that behavior tomorrow".

Behaviour outcomes should be as binary as possible

- ex. either in bed by 8pm or not.

Don't demand too much behaviour from the child to earn a point.

- To build habits, we praise and give tokens for small bits of behavior.

- we don't start off awarding points for 1 hour of homework, but we start out by giving points for 10 minutes of homework. From there, we can expand once the habit starts to take shape.

In the beginning, keep it simple, focus and try to change one or a maximum of two behaviors but no more

- Once the behaviors develop consistently, you can stop giving points and praise for that and replace it with another behavior.

do not give points for long-term outcomes.

- ex. the program will not work if you say if you get good grades, I'll give you a car.

Point systems have the added benefit of helping the parents be more consistent, since the scoreboard serves as a cue to deliver praise more systematically.

If you are taking a vacation, consider having an isolated point program just for that trip, especially if you don't already do point systems at home.

Attending & Planned Ignoring

Attending and planned ignoring can be effective techniques with adolescents.

- try your best to ignore the bad behaviours your adolescent exhibits, and focus on positive opposites to modify behaviour.

- a good indication that you should be using strategic attending and ignoring is that you complain about how difficult it is sometimes to interact with your adolescent. Pay special attention to opportunities of positive conversations around the house, while on an errand, or in the car, or comments about his or her school day.

- tip: think of these situations beforehand so you are more aware when they do occur.

Attending

Attending is noticing when someone is doing some behavior that you wish to increase and then providing attention by praising, smiling, asking pleasant questions, talking nicely, hugging or giving the child a pat on the back.

- the effects of giving attention can be both positive or negative

- negative - if our child is continuously complaining about a chore they have to do, it can have a detrimental affect if we stop and continuously explain single time.

Naturally, negative events tend to draw our attention more that positive ones

- ex. Consider that when 2 children are playing together nicely, we tend to leave them alone. When they start fighting, that is when we attend to them.

The effectiveness of attending depends on four conditions:

- define the behavior you want to increase

- decide on the type of attention you're going to use

- ex. give praise, give acknowledgement ("I noticed you brushed your teeth without us even having to ask!")

- ensure the attention is given directly after the behaviour.

- attend to the behaviour often

Planned Ignoring

Planned ignoring is when you deliberately don't give attention to a behaviour.

- ex. don't look at them, talk to them, start talking to another person etc.

The effectiveness of planned ignoring depends on four conditions:

- define the behavior you will be ignoring

- decide which kind of planned ignoring to use when that behavior occurs

- try to be consistent and use planned ignoring whenever that specific behavior occurs that you wish to decrease.

- be sure to attend to the positive behavior, since planned ignoring not effective by itself and must be coupled with attending

- this is necessary, because we need a positive behaviour to replace the negative behaviour.

Consistency is key when it comes to correcting a behaviour via planned ignoring. Even if you are successful 90% of the time ignoring the behaviour, it will be that 10% probability that the child will be motivated by, and the behaviour will persist.

- this same effect is present in gambing psychology, where when a reward occurs once in a while and is unpredictable, behaviour can persist for a long time.

Behaviours tend to get worse when starting a planned ignoring routine. This only lasts for a few days, and should be followed by improved behaviour thereafter. Try your best to ignore the increase intensity.

Punishment

Very mild and brief punishment can be helpful when that punishment is a supplement or a minor part of a larger program to reinforce behavior. However, the emphasis has to be on the positive opposite.

Steps to effective punishment:

- decide the behavior you want to decrease.

- decide the behavior you would like to replace that other behavior (ie. positive opposite) so that you can attend to and praise it.

- decide how you will reward that new behaviour

- decide on the punishment that will be used. It should be mild and brief, since more intense punishments have shown to be no more effective, and also bring out more negative side-effects.

- the punishment should be determined ahead of time to avoid impromptu punishments, since impromptu punishments tend to be long and severe

- ex. time out from reinforcement, loss of a privilege for a short period of time, loss of points if you're using a point program, or even a mild reprimand.

- make sure instances of the praise greatly outnumber the instances of the punishment.

- ex. if you gave your child time out four times this week, it would be critical to administer attention for the positive opposite at least twice as many times.

Three main types of punishment

- presenting something undesirable or negative after a behavior. In each case, the child does the undesirable behavior and something is presented.

- ex. reprimands, shouting, or hitting a child.

- taking away something positive after a behavior.

- ex. taking away an activity, a privilege, or some planned positive event, give time out. In point programs, taking points away for some misbehavior would be another example

- requiring some effort or some task that has to be performed. This usually consists of using a chore or cleaning up something as a penalty.

- ex. if a child breaks something, he would have to clean up the mess as the penalty or work on some other chore.

Traditional punishment is not very effective for developing behaviours, nor eliminating negative behaviours.

Negative side-effects of punishment

- emotional reactions on the part of the child who is punished. This may include crying, arguing, or even striking a parent.

- escape and avoidance. When a parent delivers more punishment than praise, children often try to distance themselves from the person who punished them.

- Consider that the punishment you give may be creating a negative association that we want to avoid.

- ex. when punishment consists of extra homework, staying after school, and even exercising, that creates a negative association for the child. This is something we must be careful to avoid.

- Consider that the punishment you give may be creating a negative association that we want to avoid.

- an increase in aggressive behavior. When a person punishes, the child is more likely to retaliate by hitting the punisher. This is especially likely when the punishment involves physical contact in some way.

- ex. if a parent uses hitting as a form of punishment, that'll lead to aggression and teach them to punish their peers in the same way.

- ex. if the parent tries to physically force or take a child to time out

Timeout from Reinforcement

Time out consists of a brief period of time in which the child does not have access to the usual rewards in the situation

- ex. the rewards might be just being in the presence of others, receiving parent, teacher or peer attention, or participating in some activity or game that is going on

During time out, there is no talking or playing with the child.

The place of timeout must not be somewhere where the child can not have fun or find interesting things.

Timeouts have nothing to do with thinking about what they did wrong— they are about withdrawing attention for a period of time.

It is not necessary to send the child to their room; even having them stay in the same room that the negative behaviour occurred in is fine

"reinforcement" is a technical term for rewards

There are five ingredients for using time out.

- decide exactly what behavior will serve as the basis for asking the child to go to time out.

- determine the positive opposite behaviours, and praise when they occur

- without this, positive behaviour change will not occur

- decide what and where this timeout will occur.

- decide how long timeout will last (1-5 minutes is sufficient)

- longer tiemouts are not more effective

- have a backup punishing event (preferably loss of privilege) that will be used if the child refuses to go to timeout.

- the punishment should not exceed 24 hours

- ex. "if you do not go to timeout now, you will lose your tv privilege for tonight. You have a choice.". Give them 30 seconds or so, and if they still refuse, deploy the punishment, and simply walk away without arguing

- explain how timeout works to your child while everyone is calm and happy. Simulate to the child what it is like when getting a timeout (again, while everyone is calm any happy).

Never

- physically bring your child to timeout

- physical contact during punishment leads to aggressive behaviour

- lock a child in the room

- give more than a couple warnings about going to/staying in timeout.

Avoid

Some general things to avoid:

- when a child is angry, don't get them to talk about their anger

- talking about aggression will not reduce aggressive behaviour, and may in fact increase it.

Playful parenting

When everything is going smoothly, playful parenting is about having fun together. The rest of the time, it's about drawing children out of their isolation. Play is a child's natural way of recovering from their daily emotional upheavals. Therefore, the better we are at playing with a child at their level, the better we'll be at helping them reconnect to us.

- reconnection might be as simple as making eye contact with a baby just after their outburst has subsided.

It’s the parents job to seek out the connection, but the child’s job to set the terms on how they are going to connect

Kids wants to relieve their frustration through play. When they get a needle at the doctor, they feel frustrated and powerless and the first thing they want to do when they get home is play doctor. Be the patient for them

There are four circumstances when children need more active participation from adults:

- When they are having a difficult time, connecting with peers or adults.

- When they seem unable to play freely and spontaneously.

- When things are changing in their life, such as the start of kindergarten, the birth of a new sibling, a death or divorce in the family.

- When they are in danger.

It’s when kids need parental attention the most that we are least equipped to give it to them

- kids need us when they are not connecting well with their peers (or us). This normally makes us feel sad, mad, bored or irritable, rather than playfully attentive.

- kids need us when they are going through transitions. But transitions are difficult for adults too. When we go through transitions, we have even less attention for our kids.

Ask children to try to make you laugh. This will give you a good idea of what they find funny.

Role Reversal

Reversing roles helps a child explore situations they are uncomfortable with and helps them restore their sense of confidence, and overcome fears and inhibitions.

- ex. When a kid has trouble being sent to the principles office, imagine you are the misbehaving student and they are principal dishing out the punishment.

- ex. When your child is learning how to ski and is falling often, fall often yourself and play the part of bumbling adult who can’t do it properly.

Universal Translator

We need to be able to properly tune in to our children's behaviour, taking any troubling, annoying or infuriating words/action from our toddler, decoding it, and then responding to the decoded version of what their words/actions mean.

ex. a child walks into the classroom and hits his favourite teacher and then runs under the table

- the translation: "I want to get close to you, but closeness is scary for me. Besides, I'm angry and you probably hate angry kids, so I'll hate you first"

- the thoughtful response: "You know, I wonder if you hit me and then run under the table because you kind of want to get close to me, but you're kind of not sure. How about if we shake hands or give each other a high five whenever you come into the room?"

ex. a child says "this homework is stupid"

- the translation: I'm frustrated because I haven't mastered fractions yet. Can you help me?"

- the thoughtful response: "I'd love to help you with fractions"

ex. a child says "I hate you"

- the translation: "I haven't figured out yet how to be mad at someone I love; it's confusing"

- the thoughtful response: "I love you, and I get confugsed too when I'm mad at someone I love"

We need to remember to use this translator especially at times when our childrens behaviour seems to make no sense.

Resources

Children

Backlinks